Arguing for E-2-E approach¶

A book about Deep Learning with Vector Graphics also needs to make the point why an end-to-end (E-2-E) approach appears to be a desirable objective.

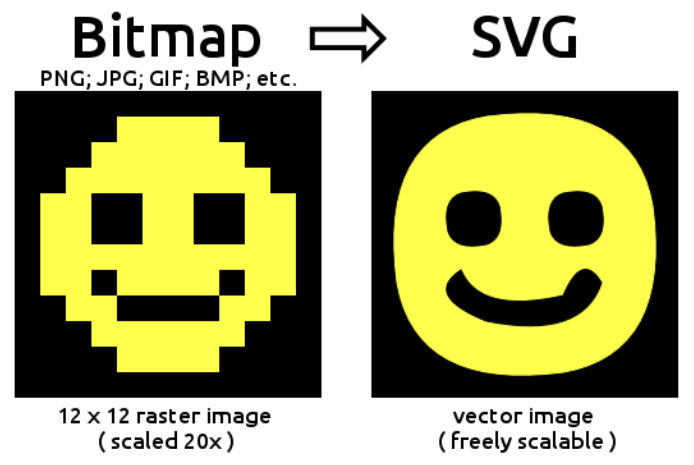

End-to-end in a Machine Learning context refers to a single model that is able to consume the available input and covers all the steps required to produce the desired output. End-to-end in this context shall refer to a generative Deep Learning model that is fed vector graphics and can directly output vector graphics. If vector graphics are the desired output but the model only generates raster images that still need to be vectorized, then this would not be called end-to-end.

End-to-end in this context shall not exclude multi-modal approaches where, in addition to the vector graphic, other types of inputs are used, such as text descriptions or the corresponding raster image. Multi-modal may even be a required setting for some problems.

Here are a few bold claims (that may still require evidence):

(1) End-to-end is more efficient and faster

(2) End-to-end is more effective

Rasterising a vector graphics leads to information loss

End-to-end helps maintain symmetries, perfect angles, clear color boundaries etc.

Current vectorizers are doing a poor job

These arguments shall be elaborated on in the following. Please contact the author if you feel the arguments are invalid or could be expressed more clearly or powerfully.

Note

It is not obvious at all which process is better:

A generative end-to-end model

A pipeline of two models: A generative model trained on rasterised vector graphics, and one model that has been trained to convert raster images into vector graphics (e.g. Im2Vec) It could be the case that a pre-trained DALL-E 2 type model is much better at producing the creative results. The potential downside of hard-to-vectorise images could be eliminated if the model has been restricted to simple outputs, such as black-and-white images or flat-color images.

1. End-to-end is more efficient and faster¶

Training on SVG could be much faster since vector graphics can store information much more efficiently than raster images. This is obviously the case if an image has been designed as a vector graphic from the start. The rastered image file will be much larger and even “empty” pixels need to be described using their RGB(A) values.

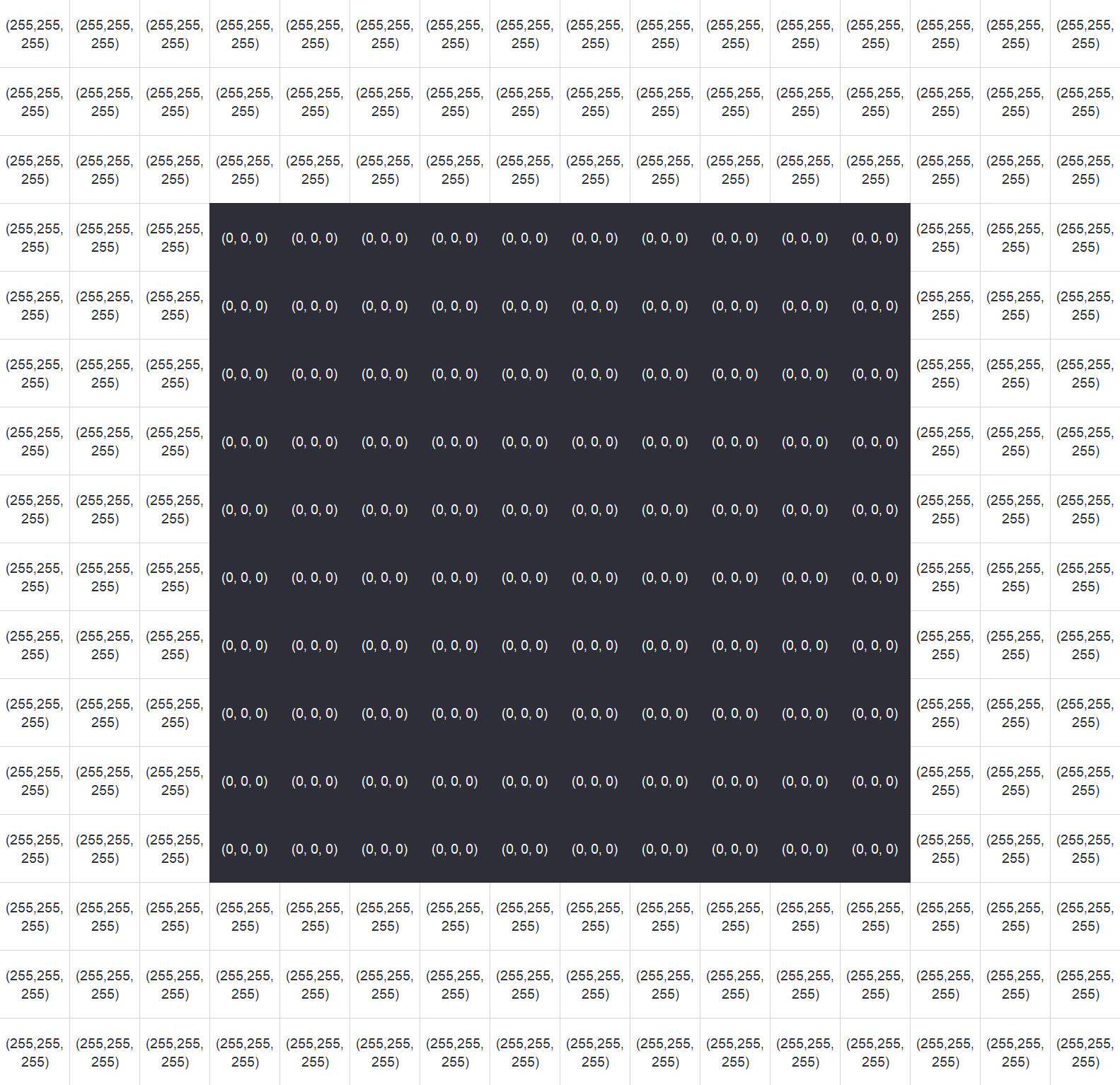

Compare a simple 10x10 rectangle in a 16x16 image as vector graphic against its rasterized version.

Fig. 5 Simple 10x10 rectangle in a 16x16 image; illustration of how a raster image would store the information using RGB pixel values¶

Even at the low resolution of 16x16 pixels, so much more information needs to be processed than in the equivalent vector graphic. 256 pixels in the image times the 3 values for each RGB channel.

In comparison, the SVG code of the rectangle (decomposed to a path) would look like this:

<svg width="16" height="16">

<path

d="

M 3, 3

L 13, 3

L 13, 13

L 3, 13

z

" />

</svg>

And this is also how a vector graphics editor would show the rectangle – as a closed path of just for connected points.

Fig. 6 Simple 10x10 rectangle in a 16x16 image; screenshot of how the vector graphics editor Inkscape shows the SVG¶

Training DeepSVG, for example, on a small dataset using an RTX 3090 takes less than an hour. Training models for raster images generally takes much longer: days, if not weeks.

2. End-to-end is more effective¶

If obtaining SVG is our goal, then the approach of using generative models for raster images and to then convert their output to vector graphics is futile. Current generative models are not conditioned to produce output that is easily converted to vector graphics, especially when it comes to colour images (as opposed to black and white images). And such a conditioning would not be trivial.

2.1 Rasterising a vector graphics leads to information loss¶

Unlike raster images, vector graphics contain additional structural information (e.g. how shapes are represented, how low-level elements are grouped together to form high-level shapes, …).

Learning about the composition of an SVG is only possible if this information is fed into the model. A rasterised image has lost that information.

2.2 End-to-end helps maintain symmetries, perfect angles, clear color boundaries etc.¶

Many logos and icons make use of perfect symmetries and perfect 90° angles. This information could be maintained if both input and output are vector graphics. Colour inputs to a generative model for raster images often lead to watercolor effects where boundaries between shapes get blurry.

Example:

Have a look at the following figure which shows 4 different icons which have been reconstructed by a VAE. The icons were originally SVG icons and presented to the VAE as 128x128 rasterised images. Thus, the VAE was trained on raster images only.

Fig. 7 Unclear color boundaries (VAE-reconstructed icons; VAE was trained on 128x128 pixel rasterised vector graphics)¶

While the black and white characters would be relatively easy to vectorize, the icon in the upper right corner would not. The outline of the overall shape and the check mark have been reconstructed very well. But the blue shapes that make up the shield bleed into each other and now have irregular color gradients.

In the following figure, the target icon in the lower right corner looks like a watercolor painting. Especially this watercolor effect makes vectorizing these results very difficult.

Fig. 8 Undesirable watercolor effect (VAE-reconstructed icons; VAE was trained on 128x128 pixel rasterised vector graphics)¶

The figure below shows a “location pin” generated by DALL-E trained on a custom dataset of raster images (after 7 epochs). There were approximately 8,000 examples in this “location pin” class. Practically all examples were symmetrical (could be mirrored along the y axis) and used a perfect circle as shape in the centre. The generated example has lost these properties. For icons, this type of fidelity or precision in the reproduction of concepts matters.

Fig. 9 Icon of a “location pin” generated by DALL-E trained on a custom dataset of raster images (after 7 epochs)¶

DALL-E is only implicitly learning the symmetry in the training examples; there is no explicit conditioning on these properties.

2.3 Current vectorizers are doing a poor job¶

Current tools for converting a raster image (e.g. a PNG) to a vector graphic (“tracing” or “vectorization”) are still doing a poor job.

Main issues with current vectorizers:

No context-aware tracing

E.g. not prior classification of objects and if they should be round or edgy

E.g. the bottom of a heart shape becomes round (–> incorrect points / edges)

Identical elements of different sizes may get traced differently.

No resolution-aware tracing

At low input resolution, tracers may start to follow pixel borders like steps

E.g. a vectorizer may fail to recognize that a shape was likely a circle even though it is now a 20x20 pixel blob with step-like sides

No shape-aware tracing

Images get vectorized as paths – even though some aspects could be vectorized as basic shapes, e.g circles, rectangles, ellipses

Potentially incorrect trade-off between accuracy and number of points

Vectorizers rarely produce elegant results with minimal number of points

Over-use of points vs. a smart use of bezier curves and their handles

No or poor detection of colour gradients

No consideration of symmetry

Many glyphs and icons have symmetries of some kind (reflectional, translational, rotational, …)

Current vectorizers are insensitive to symmetries

Tracers do not understand how humans compose images from multiple shapes (potentially overlapping, potentially half-transparent), e.g. shadows

SVGs just have too many parameters and an intractable complexity for current vectorizers to correctly guess them all given a raster image

Even the Deep Learning-based vectorizers Im2Vec cannot fully address the above issues. Im2Vec has been trained on raster images only and lacks awareness of the true underlying composition of the original vector graphics.

Examples¶

Example 1:

The image below shows the “Octocat”, Github’s mascot.

Fig. 10 Github’s mascot Octocat¶

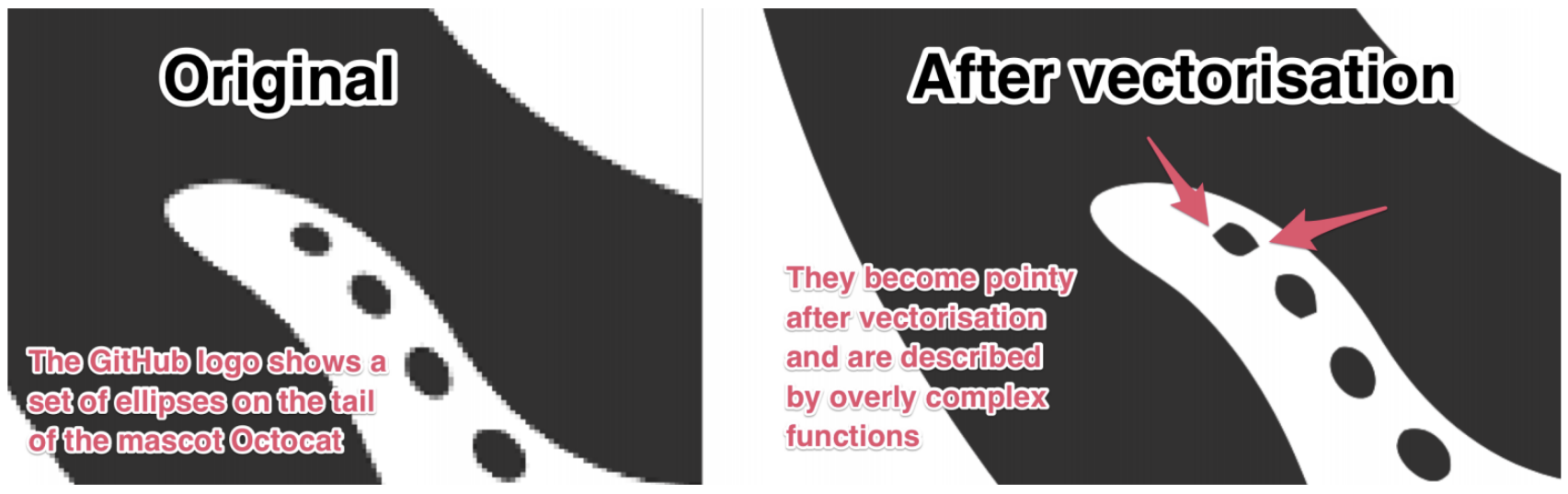

Note the ellipses on the octocat’s tentacle-tail in the figure above. Vectorizing a low resolution version of that section of the image leads to a poor result, see the figure below:

Fig. 11 Current vectorizers are still performing poorly. In this case, the used tool was vectormagic – still one of the better tools out there and not free.¶

The low resolution results in the smaller ellipses to have corners in the vector output. It appears that the vectorizer has no understanding that the resolution of the input is low and pixel edges and corners should not be traced too closely. The vectorizer also has no contextual understanding that there is a symmetry in these shapes: all of these are ellipses of different sizes.

Example 2:

In another example, see figure below, an image loses its perfect symmetry through vectorization.

Fig. 12 Example from imagetracerjs¶

Example 3:

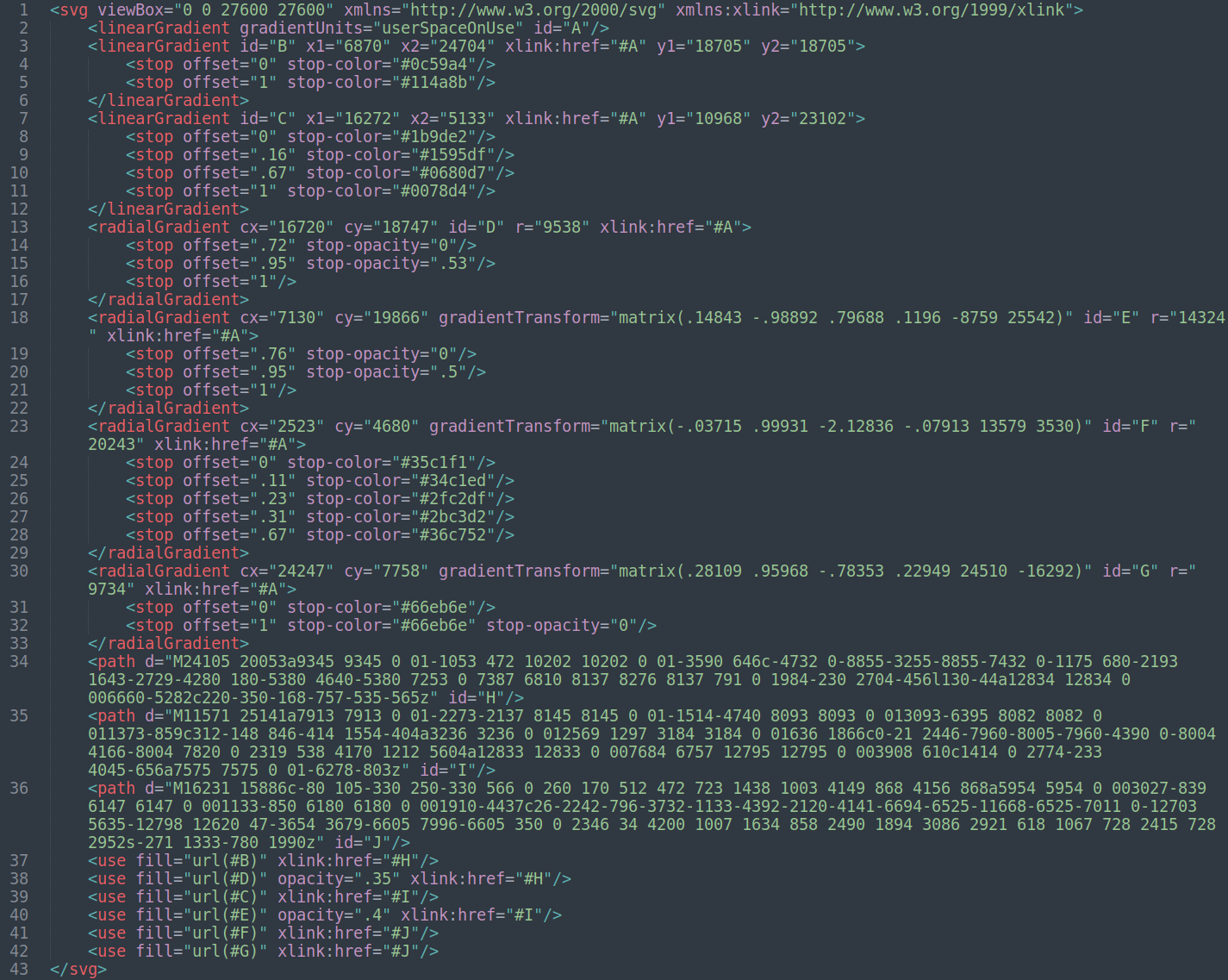

Vector graphis, such as SVG, can make use of linear and radial gradients. This can produce visually pleasing results, such as this logo below:

Since this logo was designed as an SVG, we know it is possible to design such a logo as a vector graphic. Here is the SVG code for the logo above:

Fig. 14 SVG code of the Microsoft Edge logo¶

However, current vectorizers have a hard time converting a rasterized version of the logo back to a vector graphic. These algorithms have no understanding of what (potentially overlapping) shapes are required and what shapes need to have what type of linear or radial gradients. There are too many parameters at play for pre-Deep Learning algorithms to work well.

Fig. 15 Screenshot of the vectorized Microsoft Edge logo; vectorized using vectorizer.io. The vector result is much more complicated than the original SVG and no where near the original in terms of quality.¶

Example 4:

Consider the reconstructed icon below:

Fig. 16 Lacking contextual awareness of current vectorizers¶

Current vectorizers will not understand that the icon consists of two identical hearts. The black outline on top, and the orange heart underneath and slightly offset.

Conclusion regarding poor vectorizers¶

Because current vectorizers are performing poorly (and will hopefully soon be replaced by smarter Deep Learning-based algorithms), there is a need to output vector graphics directly. Instead of attempting to output raster images and only then vectorize them.